The War on Drugs: the Worst Addiction of All

By Max Harstein

A Twenty-Fifth Century Ensemble Production

To read a free version of the entire book, click here [PDF].

Copies are available for purchase

Selected Excerpts

Introduction

I am now seventy-three years old and like most every one of you I have lived in a

society that accepts the draconian prohibition laws (War on Drugs) as a normal part of life.

These ineffective laws, most of which date from 1919, only changed focus in 1932 with

the repeal of alcohol prohibition. Two years later, marijuana was added to the list of

prohibited substances.

The political arena, the justice system, and the press, by their creation, enforcement,

and acceptance of these laws, have created an unremitting wave of propaganda, which

results in a massive worldwide brainwashing. Thus, this unconstitutional set of laws has

escalated into a frenzy of persecution that most closely resembles the “Spanish

Inquisition.” This insane “War on Drugs” is the contemporary moral equivalent of the

“Spanish Inquisition.”

This book shows the truly evil nature of prohibition and the real reason it has lasted

so long, done so much damage, and is still being endured. It also shows how the actual

effect of the “War on Drugs” functions as a taxpayer subsidy to organized crime. When

responsible Middle America comes to its senses it will release the spell of these bad laws

and end this terrible cannibalistic, negative syndrome. Only then will our God-given

constitutional right to the pursuit of happiness be restored.

Chapter Nine – A Tragic Personal Experience Caused by the “War on Drugs”

This story is a very personal one. It¹s about my own experiences and the tragic

death of Bob, a very dear friend. In order to protect everyone involved in this true story, I

have changed the names. When I first met Bob, he was a tall, handsome, young blond

piano player of obvious Scandinavian ancestry. He had migrated to the West Coast from a

northern Midwestern state that borders Canada and the Great Lakes. He spent his

childhood and adolescence on a family farm owned and run by his parents. Like a good

farm boy, he was able to fix his old Volkswagen bug, do carpentry, electrical wiring, and

all necessary maintenance. He was a college graduate, with a grade school teacher¹s degree.

Above all, he was a very good piano player.

We always enjoyed playing together. These good feelings created the inspiration for

fiery, yet cohesive maximum freedom within an accepted formal structure, playing

together and staying together by a process of spontaneous consensus. When disputes about

the music or its performance develop in a band, even the best musicians may have trouble

staying together. It¹s all about attitude; that¹s half the battle.

Bob¹s attitude was the greatest. He was helpful, careful not to overplay, but always

there. He had a way of being open to change, looking for the new, never playing two

choruses the exact same way. That quality, plus his deep musical knowledge, made him an

exciting, original, and never boring musical companion. Bob was a master of the technique

of voicing or substitution of alternative chords that allow the maximum number of choices

for the soloist. Not every piano player knows how to do this as well as Bob did. The

band¹s main function was to provide the best place for visiting musicians to sit in and jam.

The stage was open to whoever could play. With Bob, Chuck Thompson on drums, and

myself on bass, we had a good rhythm section.

Bob was married to a gorgeous, healthy, young blonde farm girl with whom he

had grown up. They had met in grade school and become childhood sweethearts. We will

call her Ilene. Even after three children, Ilene was still a knockout. She had long blonde hair

that hung down to her waist when it wasn¹t braided. With their three tow-headed children,

two boys and a girl each separated by a year, they were a striking model family.

This story took place in the late fifties and early sixties. Bob and I were the same

age. We had been born during the Depression, before the atom bomb, before pervasive

worldwide pollution, and before the Second World War, when things seemed a lot simpler

and less paranoid. Those brief years of our young lives were filled with a kind of hope,

peace, and innocence that helped to create a calmer, more positive point of view than may

be common today. That attitude, combined with the childhood experience of growing up

on a Midwestern farm, made Bob an easygoing, calm, gentle, giving kind of guy. He loved

his kids and spent much of his time with them.

When they first came to California, Bob worked in the public school system

teaching music and science to fifth and sixth graders. They settled into city life in San

Francisco and Bob met and played with local musicians. Eventually, he was able to realize

his goal of working full-time as a jazz musician. Ilene also worked part-time as a

receptionist in a downtown office. After Bob became a full-time player, he would be with

the children in the daytime while Ilene was working and she would care for the children at

night while Bob was working. They lived in an antique house that they were gradually

fixing up, carving a beautiful, nostalgic carpenter¹s delight from a big-city slum dwelling.

Bob¹s dream of coming to a big city with really good jazz players and working as a

full-time musician was being realized. I¹m not really sure what Ilene¹s dream was, but after

knowing her for a while, it seemed to me that she was still looking for love. Ilene had an

active sense of humor. She was strong, outspoken, but not a compulsive talker. She was a

good mother who loved and enjoyed her children. She could type, bartend, waitress, cook,

sew, keep a clean house, and write poetry which she kept very private. She was a well-

rounded, talented person. When I met Bob and Ilene, they seemed to have the kind of

marriage for which everyone longs.

Bob and I met in a low-rent basement jazz club in the North Beach, San

Francisco¹s Italian and artist¹s community at that time. The club was under an Italian

restaurant and grocery store. It had been a much larger speakeasy during Prohibition. Most

of the available space was not being used. Simple plasterboard walls enclosed the long,

narrow bar and one row of tables and chairs, with an aisle in between them. The place

served only beer and wine, along with snacks, coffee, and soft drinks. To add to your

confusion, we shall change the club¹s name and call it the “Jazz Underground.” Most of

the space of the old speakeasy was unused, or simply used for storage. There was a rather

large band room, entered only from the bandstand at the far end of the room. The band

room was furnished with decomposing overstuffed couches and wooden beer cases.

The bar business was owned by two drummers who took turns playing music and

tending the bar. The somewhat full-time bartender was “Big John,” who also served as the

bouncer. Big John was an amateur drummer and poet. He was also an alcoholic and not

always available to perform his duties. He was a large, dark-haired Irishman with, when

not too far out, a very lovable disposition and a gift for conversation. These endearing

qualities made it easy to overlook his problems with strong drink. Big John was one of the

first poets to read with jazz accompaniment at the Underground.

This was all happening in the late fifties, when Herb Cain coined the term

“Beatniks.” While we hated the name, we were in the process of defining what he meant

by it. To ourselves, we were just jazz musicians, willingly suffering the economic

hardships of the artist rather than the dulling nine-to-five conformity of the Eisenhower era.

Palling around with painters, poets, writers and street philosophers, we thought of

ourselves as Bohemians. San Francisco was in cultural ferment, especially in North Beach,

which was the center of the action. It was one of the city¹s best weather neighborhoods.

Older retired Italians owned most of North Beach. Chinatown, with its wonderful

inexpensive food, was just around the corner. Rents were low and food was cheap. You

could get a really delicious home cooked Italian dinner with soup, salad, antipasto and a

main course with plenty of bread and vegetables and dessert for a buck and a quarter. In

Chinatown, it was even cheaper.

Bob Kaufman was reading his poetry on the street in North Beach and because it

sometimes contained cursing and other expletives, he was ordered to stop. When he didn¹t,

the police beat him every time they found him out there doing it. The beatings finally

ruptured both his eardrums and rendered him deaf, but he never stopped writing or reading

in public and later became famous through the publication of his work.

Nonetheless, these confrontations with the establishment eventually drove the

poets, painters, sculptors and musicians out of North Beach and when the sons of the

elderly or deceased took over, they gentrified the old Barbary Coast, a one-block-long

section of strip joints, and then turned all of North Beach into (what had once been only

one block) topless dancing and sex clubs. It was a virtual red-light district. Of course, all of

this was done with the idea (fantasy) of cleaning up the North Beach district. This change

was epitomized by the Old Italian haberdashery on the corner of Broadway and Grant that

was turned into the topless club in which Carol Doda danced. The club was later to be the

site of a strange, on-stage murder. A male dancer was crushed under a grand piano that fell

on him.

Bob Kaufman, whom we mentioned before, was one of the many poets that read

with jazz accompaniment at the Underground. Others included Lawrence Ferlingetti, Bob

Briggs, Gregory Courso, Ruth Wiess and Nancy Buetti.

Bob, the club owner and piano player and his wife and Ilene were very much

behind the jazz and poetry movement. Their backing of the process at the Underground

gave jazz and poetry a stage in a time when such spaces were very rare or nonexistent. We

had one or more poets on stage every Wednesday, largely due to Bob and Ilene¹s support.

Many jazz players hated it and some were very uncooperative, but not at the Underground.

We did our best to put the poets in the foreground, in front, featured like a vocalist.

Many players don¹t like playing softly and holding back for vocalists either, but that¹s what

you have to do, so they can be heard distinctly. It¹s even more so for a poet. It was always

so frustrating and sad to see a poet forced to shout at the top of his lungs to be heard over

the music. Even if heard, the words tended to lose their meaning. Bob was always

musically very supportive of the poets.

I had the poets who were reading each Wednesday evening over to my studio

apartment in the afternoon and rehearsed with them what they were going to do, working

out little arrangements so that they had enough space and we had some too. The poets were

always very eager to do this planning and rehearsing, and it made for some very original

and sophisticated performances.

I shall digress from the story of Bob and Ilene to explain how it was that I became

the house bass player at the Underground. I came off a very unpleasant road tour with a big

band. The experience was so stressful that I gave up playing for a while. I went to live with

my parents and help my father build his furniture store in San Jose. This was a way out of

the stress I was experiencing and not unpleasant, but I missed playing, I missed my friends

and the jazz scene. I missed music, so I would spend a weekend evening in San Francisco,

catching the big names as they came through and usually ended up at the Underground.

People were always glad to see me and Bob would insist that I play a set or even just a

tune.

Bob was so kind and appreciative that I became a regular weekend player and

started practicing again. About the time the store was ready to open, the construction

having been completed, Bob asked me to take the job as the house bassist.

My schedule was to play six nights a week, five hours a night from nine until two,

and twice on Sunday, three to six and then nine until two. I was thrilled to take the job,

even though (for all those long hours) it paid exactly the same as my first steady job ten

years before, sixty-five dollars a week. By that time, Bob had bought into the Underground

and was the third partner. He had a lot of influence at the club, and pulled me right in. I

moved back to San Francisco, got a large apartment just around the corner from the

Underground where I could paint and walk to work. I shall forever be grateful for Bob¹s

encouragement and sponsorship back into the jazz world.

I remained on the job for eighteen months, the longest, steadiest, six-nights-a-week

club job I¹ve ever had‹or for that matter, any other employment. But, especially in music,

coming to work at the same place, same time, same band, night after night, gets real stale.

Without Bob¹s special talent for open playing, his ability to be moved, and the ability to

listen and change his mind, I could never have lasted that long.

If there was one thing that Bob proved to be absolutely incorruptible about, it was

his concern for the quality and upward advancement of the musical performance on the

stage at the Underground. During my eighteen months there he allowed me to scout young

talent new in town so we could use them on our gig before their ability and reputation

brought them better offers of more money than we could pay. We used Brew Moore who

was well known but had some difficulty holding a job because of his alcoholism. Brew

never let us down musically, but after the job he needed a babysitter to keep him from

harming himself.

Everyone connected with it was giving a major part of their lives to keep the

Underground going, especially Bob and Ilene. As I mentioned, I lasted a year and a half

until the stress, responsibility, the slowly declining economy coupled with the gradually

rising inflation and the paltry fixed pay finally got to me. It must have been for similar

reasons that Bob and Ilene¹s marriage broke up. Ilene took the kids and left town to settle

in Big Sur with Bob¹s best friend, a young artist.

The next bit of this drama to unfold was a fire in the Underground that ended its

operation, but only temporarily. With the money from the insurance and help from the

owner of the property, who was solidly behind the enterprise, they expanded, remodeled,

went into debt, hired the manager of the “Jazz Workshop,” and tried to go big time. I was

asked to return and play in the house rhythm section, which included Melvin Ryan on

Piano and the late Smiley Winters on drums.

We opened the new “Jazz Underground” with Dexter Gordon. Dex had just been

released from prison in Los Angeles (for a drug bust) and was in magnificent shape, tall,

slim, healthy and playing marvelously. For me, it was a “dream come true.” We kept Dex

for a month instead of a week and things seemed to be going good. However, after a few

months the massive expenses of the operation and the manager¹s phone bills bankrupted

the club and it closed its doors after the Ben Webster, Jimmy Witherspoon show.

Bob then followed Ilene to Big Sur and took a position teaching school so he could

be near his kids. He also took over the management of a small rustic motel on Highway 1,

which is the main road through Big Sur country. The motel, although small and somewhat

grungy, had a bar and restaurant that Bob turned into a jazz club on weekends. They catered

to the organic food crowd, serving mostly vegetarian organic meals. He and Ilene were on

friendly terms, the friendship renewed with his artist friend with whom Ilene was now

living. Bob was in daily contact with his children, whom he taught in the small rural school

they attended.

In Big Sur Bob grew a beard and let his crew cut grow until he looked like a

disciple. He seemed to be thriving. He lived in quarters at the motel. His children, Ilene and

her artist lived in the rugged hill country off the main road. If you are at all familiar with

Big Sur country, you will know that in many ways this situation was not too far from

idyllic.

In my own life progression I had once again left the stress of the music business

and retired to a studio in Mexico in a small village high in the mountains in central Mexico,

where I sketched and painted. Missing music, I once again returned to San Jose, California

where I resumed playing jazz. My range of jobs expanded to an area just north of San

Francisco, through San Jose, Santa Cruz, Carmel, Monterey and Big Sur. About once a

month I would drive to Big Sur and play a bit with Bob on the weekend, either sitting in or

working as the bassist. After the gig we often hung out at Esholam in the hot mineral

baths.

The next big move in my life came as a result of my beautiful two-hundred-and-

fifty-year-old solo Italian string bass being stolen out of my car, which was parked on a

busy, well-lit street in North Beach. I was inside “Mike¹s” restaurant and pool hall having

a bowl of good, rich minestrone soup after my gig at the bar of a local hotel just a few

blocks away in downtown San Francisco. It was a job for piano and bass. Shelly Robbins

was the pianist. Shelly was handsome, suave, debonair, with a quick mind and brilliant

technique. He knew more tunes than anyone I have ever worked with and he swung. We

went to Mike¹s together that night as we often did. The theft was so well done that even

though I was only a few yards away from the scene with a view of my car from where I

was sitting, I was unaware that the theft had taken place.

When we finished the soup and returned to my car, I discovered that the small

wind wing window in the front door had been broken and was open. The bass was gone. I

was devastated. The bass was the best instrument I have ever played and the positions on

the fingerboard just right for my hand. That bass was so good it launched me into the

upper levels of jazz music. It has proven to be irreplaceable. I wept bitterly for many hours

over this bad luck.

Eventually, after a series of inadequate replacements, I went to Europe to find

another handmade antique bass, the equal of the one stolen. I believed, as had been told to

me, that there were many such instruments still available in Europe. Unfortunately, when I

started looking in England, France and Spain, I was told all the good ones had been bought

and taken to the U.S. Nevertheless, I found a fair replacement and had the extremely good

fortune to play for a month with Kenny Clark and Bud Powell at the Paris “Blue Note.”

When I returned to the States, I rented a loft in New York on the Bowery, at the

corner of Third and Houston. It was the center of the Bowery. Both sides of the street were

littered with men, mostly veterans, in all the various stages of drunkenness, from

staggering to out cold. I loved my loft but the action outside became unbearable and I left

the “Apple” in 1963 after President Kennedy¹s assassination and returned to California.

Back in the sunshine state, I settled in with a piano player and jazz disc jockey. He

was a good and generous friend, a good piano player, and lived on a houseboat in Marin. I

started out again on the West Coast and looked up old acquaintances to let them know I

was back.

I inquired about Bob and learned that my dear friend Bob had died of an overdose

of heroin and his body had been found in his pickup truck on the side of a little used road

in the Big Sur Mountains. As the story unfolded after the first shock of it‹because to my

knowledge Bob had never used hard drugs‹it turned out that another longtime friend of

Bob¹s (a talented jazz drummer whom I shall call Billy) had just returned from a world

tour. With him, he had managed to bring back some extremely strong “horse” from Japan.

This was an underground product for which Japan had been noted. Billy was a

heroin addict, a loose living kind of guy and, as is often the case, a person who often used

and misused other people. Apparently, because Billy was acclimated to the potency of this

kind of heroin; he presumed that everyone else would be. He had persuaded Bob to try

some and unfortunately, because of his lower tolerance of the drug, Bob overdosed.

Of course, Bob¹s dabbling with the strong heroin was a tragic mistake for him to

make. However, such a medical emergency is not difficult to handle. A saline solution

administered intravenously can usually bring the victim back from the edge. These people

were in a vehicle and could have brought Bob to the emergency treatment facility, but that

building also housed the fire department and the local police station for Big Sur.

Obviously, because of this prohibition we have come to call the “War on Drugs,” all those

in the car would have been arrested and sent to jail for long prison sentences. Considering

that probability, Bob¹s erstwhile friends tried, I¹m sure, to bring him back themselves, and

in the process, being unable to do so, waited too long for any treatment to succeed. And so

his body was left on the side of the road, yet another victim of the “War on Drugs.” As we

ponder this terrible, unnecessary tragedy, hundreds and eventually thousands of citizens are

paying with their lives for the massive blunder of driving drug use underground.

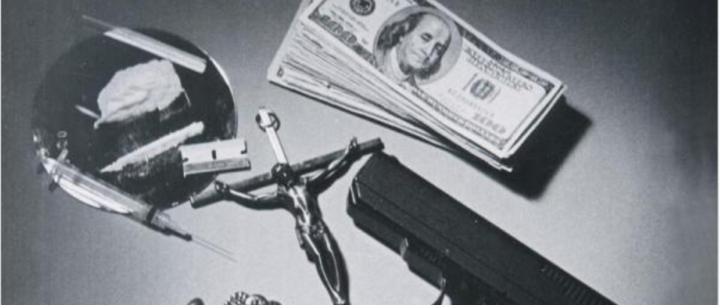

This is just one personal example of what the “War on Drugs” is really doing to

people. It is directly responsible for most of the deaths due to an overdose of hard drugs. It

is directly responsible for the artificially high prices of illegal drugs, making them so highly

profitable that the temptation to exploit this “Black Market” is irresistible for both the secret

financiers on down to the lowly street dealers. It is directly responsible for the pervasive

corruption of the law enforcement and justice systems, and linking them to organized

crime. It is directly responsible for diverting tax revenue from the social safety net to the

giant pork-filled prison system. It is directly responsible for eroding our constitutional

rights, our once free society, our free market, and our right to the pursuit of happiness. It is

directly responsible for so much misery that it simply must be ended and replaced with a

more sensible and humane system of control and regulation.